Erstwhile Okie on Saint Mark's Place. Frustrated novelist, satisfied father.

Jesus I know, and Paul I know; but who are ye?

In church this past Sunday, the Psalm reading came from Psalm 90. One line of it struck me: Make us glad according to the days wherein thou hast afflicted us. The bit that struck me was in the idea that God afflicts us.

I read and enjoyed a book recently, recommended to me by my church rector: The Will of God by Leslie D. Weatherhead. The basis of it is to critique those that might, in the midst of suffering, say that it is God's will; that it is never God's will for us to suffer, but that in our liberty, we are not restrained from acts of which the natural consequence is suffering.

While I think this view has a lot to commend itself and affords us a concept of a loving God better aligned with our earthly definition of love, it replaces a God who would intentionally injure us with One who merely lets us be injured. I think both have downsides.

Either way, the verse in question leaves no doubt in a straightforward reading that God does not just let us be afflicted, He afflicts us.

It might be splitting hairs, but I personally favor a God who, seeing me running into traffic would snatch and beat me rather than watch on, determined to let me learn my lesson naturally, even if the injuries were equal in either scenario.

I don't know why I felt compelled to write about this, but I did, and in doing, went to review the Psalm in full and was struck further by how the line that had first caught my attention actually ranks pretty low in the litany of active cruelties described.

Thou turnest man to destruction; and sayest, Return, ye children of men... (read: An older sibling: "stop hitting yourself!")

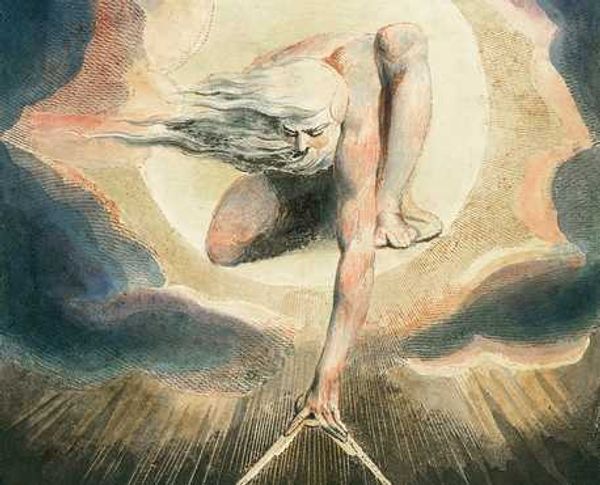

I was struck too by Before the mountains were brought forth, or ever thou hadst formed the earth and the world, even from everlasting to everlasting, thou art God. but for no reason other than that it brough to mind Job; God demanding of him Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth?

So it seemed especially interesting that Psalm 90 is, by tradition, the only Psalm attributed to Moses, making it the earliest, which again parallels Job, as that book is similarly cited as being the earliest written book of scripture.

What does it mean that the earliest question posed by man was why we suffer? And what does it mean that both Job and Moses, who had direct interactions with the Almighty, understood the answer to be that He willed it so?

Beats me.

But it has gotten me thinking about how dismissively I approach the Psalms, which I don't think is unusual among thoughtful Christians. They plead for God to torture enemies, they lament our unjust sufferings; all of which seems wrong through the prism of Christ's teaching. But I think it suggests that I ought to find a way to adjust my thinking rather than to somehow find clever contextualizations that bring it into alignment with how I think it ought to be.

I'm planning on trying to actively read through them with a mind for how I can genuinely pray them. I have a copy of C.S. Lewis' Reflections on the Psalms which I've never read past the introduction, but which might be a useful guide.